27. Gauss' Theorem

Let \(V\) be a nice solid region in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) with a nice properly oriented boundary, \(\partial V\), and let \(\vec F\) be a nice vector field on \(V\). Then \[ \iiint_V \vec\nabla\cdot\vec F\,dV =\iint_{\partial V} \vec F\cdot d\vec S \] The outer boundary must be oriented outward while any inner boundaries must be oriented inward. This means that all pieces of the boundary are oriented away from the solid.

d. Applications

2. Converting Volume Integrals to Surface Integrals

While Gauss's Theorem is most often used to convert a surface integral over a closed surface into a volume integral over the solid enclosed by the surface, there are a couple of applications where the reverse happens: computing the volume and centroid of the solid inside a closed surface.

Volume

The standard formula for the volume of a solid region \(R\) is \(\displaystyle V=\iiint_R 1\,dV\).

If we pick \(\vec F\) so that\(\vec\nabla\cdot\vec F=1\) then the volume becomes the left side of Gauss's Theorem and the volume can be computed from the surface integral \(\displaystyle \iint_{\partial R} \vec F\cdot d\vec S\). Four typical choices for \(\vec F\) are: \[\begin{aligned} \vec F=\langle x,0,0\rangle \quad \vec F&=\langle 0,y,0\rangle \quad \vec F=\langle 0,0,z\rangle \\ \vec F&=\dfrac{1}{3}\langle x,y,z\rangle \end{aligned}\] Using these four choices, the volume can be written as \[\begin{aligned} V&=\iint_{\partial R} x\,dy\,dz =\iint_{\partial R} y\,dz\,dx =\iint_{\partial R} z\,dx\,dy \\ &=\dfrac{1}{3}\iint_{\partial R} x\,dy\,dz+y\,dz\,dx+z\,dx\,dy \end{aligned}\] Use whichever formula is most convenient.

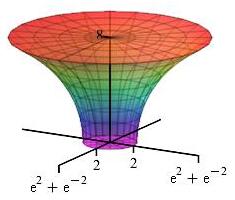

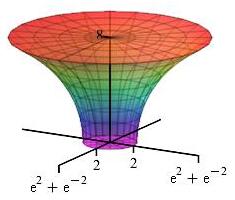

Find the volume of the vase given in cylindrical coordinates by \[ r \le e^{z/4}+e^{-z/4} \quad \text{for} \quad 0 \le z \le 8 \] as shown at the right.

Note: We can parametrize the side surface by starting with cylindrical coordinates and letting \(z=4w\) and \(r=e^w+e^{-w}\): \[ \vec R(\theta,w) =\langle (e^w+e^{-w})\cos\theta,(e^w+e^{-w})\sin\theta,4w\rangle \] for \(0 \le \theta \le 2\pi\) and \(0 \le w \le 2\).

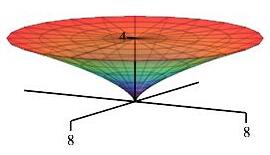

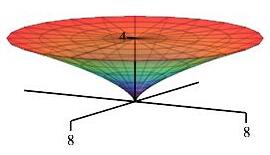

The area between the cusp \(\vec r(t)=\langle 0,t^3,t^2\rangle\) for \(0 \le t \le 2\) and the \(z\)-axis is rotated about the \(z\)-axis to sweep out a solid. Find its volume using surface integrals.

The sides may be parametrized as \(R(t,\theta)=(t^3\cos\theta,t^3\sin\theta,t^2)\).

\(V=64\pi\)

We compute the volume using the formula \(\displaystyle V=\iint\limits_{\partial R} z\,dx\,dy =\iint\limits_{\partial R} \vec F\cdot d\vec S\) with \(\vec F=\langle 0,0,z\rangle\) over the complete boundary surface which consists of the sides and a disk at the top.

Sides: The sides are parametrized by \[ R(t,\theta)=(t^3\cos\theta,t^3\sin\theta,t^2) \] The normal vector is \[\begin{aligned} \vec N&=\vec e_t\times\vec e_\theta= \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\imath} & \hat{\jmath} & \hat{k} \\ 3t^2\cos\theta & 3t^2\sin\theta & 2t \\ -t^3\sin\theta & t^3\cos\theta & 0 \end{vmatrix} \\ &=\langle -2t^4\cos\theta,-2t^4\sin\theta,3t^5\rangle \end{aligned}\] This is oriented up and in but we need down and out. So we reverse it: \[ \vec N=\langle 2t^4\cos\theta,2t^4\sin\theta,-3t^5\rangle \] The vector field is \[ \vec F=\langle 0,0,z\rangle=\langle 0,0,t^2\rangle \] and the surface integral is \[\begin{aligned} \iint\limits_\text{sides} \vec F\cdot d\vec S &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^2 \vec F\cdot\vec N\,dt\,d\theta \\ &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^2 -3t^7\,dt\,d\theta \\ &=2\pi\left[\dfrac{-3}{8}t^8\right]_0^2 =-192\pi \end{aligned}\] Disk: The disk is parametrized by \(R(r,\theta)=(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta,4)\) for \(0 \le r \le 8\) and \(0 \le \theta \le 2\pi\). The normal vector is \(\vec N=\langle 0,0,r\rangle\) which is correctly upward. On the disk the vector field is \[ \vec F=\langle 0,0,z\rangle=\langle 0,0,4\rangle \] So the surface integral is \[\begin{aligned} \iint\limits_\text{disk} \vec F\cdot d\vec S &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^8 \vec F\cdot\vec N\,dr\,d\theta \\ &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^8 4r\,dr\,d\theta \\ &=2\pi\left[\rule{0pt}{10pt} 2r^2\right]_0^8 =256\pi \end{aligned}\] Total: We complete the computation of the volume by adding together the surface integrals from the two pieces of the boundary: \[\begin{aligned} V&=\iint\limits_{\partial R} \vec F\cdot d\vec S =\iint\limits_\text{sides} \vec F\cdot d\vec S +\iint\limits_\text{disk} \vec F\cdot d\vec S \\ &=-192\pi+256\pi =64\pi \end{aligned}\]

We check by computing the volume directly as \(\displaystyle V=\iiint 1\,dV\). In cylindrical coordinates, the volume differential is \(dV=r\,dr\,d\theta\,dz\). For each value of \(z\) between \(0\) and \(4\), the \(r\) coordinate runs from the \(z\)-axis at \(r=0\) out to the sides at \(r=z^{3/2}\). So the volume is: \[\begin{aligned} V&=\int_0^4\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{z^{3/2}} 1\,r\,dr\,d\theta\,dz \\ &=2\pi\int_0^4 \left[\dfrac{r^2}{2}\right]_{r=0}^{z^{3/2}} \,dz \\ &=2\pi\int_0^4 \dfrac{z^3}{2} \,dz =2\pi\left[\dfrac{z^4}{8}\right]_0^4 =64\pi \end{aligned}\] This method seems to have been much simplier than the surface integrals!

This volume could have been found in Calculus 2 as a volume of revolution using disks or cylinders where the curve \(y=x^{2/3}\) is revolved about the \(y\)-axis. Try it!

Centroid

The components of the centroid of a solid region \(R\) are \[ \bar{x}=\dfrac{V_x}{V} \qquad \bar{y}=\dfrac{V_y}{V} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \bar{z}=\dfrac{V_z}{V} \] where the moments are \[ V_x=\iiint\limits_R x\,dV \qquad V_y=\iiint\limits_R y\,dV \qquad \text{and} \qquad V_z=\iiint\limits_R z\,dV \] Using Gauss' Theorem, the moments can be written as \[\begin{aligned} V_x&=\iint\limits_{\partial R} \dfrac{x^2}{2}\,dy\,dz =\iint\limits_{\partial R} x y\,dz\,dx =\iint\limits_{\partial R} x z\,dx\,dy \\ V_y&=\iint\limits_{\partial R} x y\,dy\,dz =\iint\limits_{\partial R} \dfrac{y^2}{2}\,dz\,dx =\iint\limits_{\partial R} y z\,dx\,dy \\ V_z&=\iint\limits_{\partial R} x z\,dy\,dz =\iint\limits_{\partial R} y z\,dz\,dx =\iint\limits_{\partial R} \dfrac{z^2}{2}\,dx\,dy \\ \end{aligned}\] Use whichever formulas are most convenient.

Find the centroid of the vase given in cylindrical coordinates by \[ r \le e^{z/4}+e^{-z/4} \quad \text{for} \quad 0 \le z \le 8 \] as shown at the right. The volume was found in the previous example.

The area between the cusp \(\vec r(t)=\langle 0,t^3,t^2\rangle\) for \(0 \le t \le 2\) and the \(z\)-axis is rotated about the \(z\)-axis to sweep out a solid. Find its centroid using surface integrals.

\((\bar x,\bar y,\bar z) =\left(0,0,\dfrac{16}{5}\right)\)

By symmetry, \(\bar{x}=\bar{y}=0.\) So we only need to compute \(\bar{z}.\) We will use the formula \[ V_z=\iint\limits_{\partial R} \dfrac{z^2}{2}\,dx\,dy =\iint\limits_{\partial R} \vec F\cdot d\vec S \qquad \text{with} \qquad \vec F=\left\langle 0,0,\dfrac{z^2}{2}\right\rangle. \] Many of the quantities were computed in the previous exercise.

Sides: From the exercise, the sides are parametrized by \(R(t,\theta)=(t^3\cos\theta,t^3\sin\theta,t^2)\). and the normal vector (reversed) is \(\vec N=\langle 2t^4\cos\theta,2t^4\sin\theta,-3t^5\rangle\). The vector field is \[ \vec F=\left\langle 0,0,\dfrac{z^2}{2}\right\rangle =\left\langle 0,0,\dfrac{t^4}{2}\right\rangle \] and the surface integral is \[\begin{aligned} \iint\limits_\text{sides} \vec F\cdot d\vec S &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^2 \vec F\cdot\vec N\,dt\,d\theta \\ &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^2 \dfrac{-3}{2}t^9\,dt\,d\theta \\ &=\pi\left[\dfrac{-3}{10}t^{10}\right]_0^2 =-\dfrac{3}{5}512\pi \end{aligned}\] Disk: From the exercise, the disk is parametrized by \(R(r,\theta)=(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta,4)\) and the normal vector is \(\vec N=\langle 0,0,r\rangle\). The vector field is \[ \vec F=\left\langle 0,0,\dfrac{z^2}{2}\right\rangle =\langle 0,0,8\rangle \] So the surface integral is \[\begin{aligned} \iint\limits_\text{disk} \vec F\cdot d\vec S &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^8 \vec F\cdot\vec N\,dr\,d\theta \\ &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^8 8r\,dr\,d\theta \\ &=2\pi\left[\rule{0pt}{10pt} 4r^2\right]_0^8 =512\pi \end{aligned}\] Total: We complete the computation of the \(z\)-moment by adding together the surface integrals from the two pieces of the boundary: \[\begin{aligned} V_z &=\iint\limits_\text{sides} \vec F\cdot d\vec S +\iint\limits_\text{disk} \vec F\cdot d\vec S \\ &=-\dfrac{3}{5}512\pi+512\pi =\dfrac{1024}{5}\pi \end{aligned}\] Since the volume was \(V=64\pi\), the \(z\)-component of the centroid is: \[ \bar{z}=\dfrac{V_z}{V} =\dfrac{1024\pi}{5}\dfrac{1}{64\pi} =\dfrac{16}{5} \] which is inside the solid.

We check by computing the \(z\)-\(1^\text{st}\)-moment directly as \(\displaystyle V_z=\iiint z\,dV\). In the check of the previous exercise, we found the volume integral is \[ V=\int_0^4\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{z^{3/2}} 1\,r\,dr\,d\theta\,dz \] So the \(z\)-\(1^\text{st}\)-moment is: \[\begin{aligned} V_z&=\int_0^4\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{z^{3/2}} z\,r\,dr\,d\theta\,dz \\ &=2\pi\int_0^4 z\left[\dfrac{r^2}{2}\right]_{r=0}^{z^{3/2}} \,dz \\ &=2\pi\int_0^4 \dfrac{z^4}{2} \,dz =2\pi\left[\dfrac{z^5}{10}\right]_0^4 =\dfrac{1024}{5}\pi \end{aligned}\] This method was again much simplier than the surface integrals!

Heading

Placeholder text: Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum