15. Polar Coordinates

a. Polar Coordinate System

2. Converting Between Rectangular and Polar Coordinates

If you need to review the definitions of the trig functions, you can use the following Maplets (requires Maple on the computer where this is executed):

Triangle Definitions of Trigonometric Functions Rate It

Circle Definitions of Trigonometric Functions Rate It

Visualizing Circle Definitions of Trig Functions Rate It

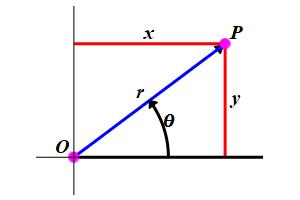

It is easy to convert between rectangular coordinates and polar coordinates because of the Pythagorean Theorem and the definitions of sine and cosine: \[ x^2+y^2=r^2 \] \[ \cos\theta=\dfrac{x}{r} \qquad \sin\theta=\dfrac{y}{r} \] Consequently:

If you know the polar coordinates \((r,\theta)\), then the rectangular coordinates \((x,y)\) are \[ x=r\cos\theta \qquad \text{and} \qquad y=r\sin\theta \qquad \qquad \text{(1)} \] Conversely, if you know the rectangular coordinates \((x,y)\), then the polar coordinates \((r,\theta)\) are found from \[ r^2=x^2+y^2 \qquad \text{and} \qquad \tan\theta=\dfrac{y}{x} \qquad \qquad \text{(2)} \]

Most often, \(r\) is the positive square root: \(r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\).

On rare occations, as in plotting, \(r\) is the negative square root:

\(r=-\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\).

It is tempting to also solve for \(\theta\) and write

\(\theta=\arctan{\dfrac{y}{x}}\), but this is not quite right.

The correct formula is:

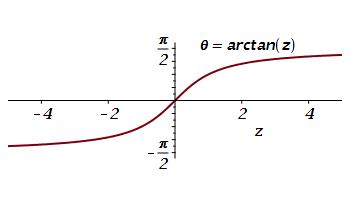

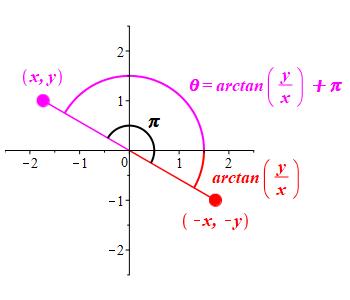

Why is the formula \(\theta=\arctan{\dfrac{y}{x}}\) not always correct?

Looking at the graph of \(\theta=\arctan{z}\) we see that \(\arctan\) always produces an angle between \(\dfrac{-\pi}{2}\) and \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\), which is in quadrant I or IV.

When the point, \((x,y)\), is in quadrant II or III (where \(x\) is negative), the formula \[ \theta=\arctan{\dfrac{y}{x}}=\arctan{\dfrac{-y}{-x}} \] gives an angle in quadrant IV or I respectively. We fix this by adding \(\pi\) or \({180^\circ}\) to the \(\arctan\): \[ \theta=\arctan{\dfrac{y}{x}}+\pi \]

\[ \theta=\arctan{\dfrac{y}{x}}+ \begin{cases} 0 \quad \text{if} \quad (x,y) \quad \text{is in quadrant I or IV} \\ \pi \quad \text{if} \quad (x,y) \quad \text{is in quadrant II or III} \end{cases} \]

However, in practice, we usually use the equation \(\tan\theta=\dfrac{y}{x}\) and adjust \(\theta\) to give the correct quadrant. On the rare occasions when we take \(r\) to be negative, we must add \(\pi\) to these values of \(\theta\).

For the point \(P\) with rectangular coordinates \((-\sqrt{3},1)\), find polar coordinates for \(P\) with a positive \(r\).

Algebraically, \[ r^2=(-\sqrt{3})^2+(1)^2=4 \qquad \text{and} \qquad \tan\theta=\dfrac{1}{-\sqrt{3}} \] The positive solution for the radius is \(r=2\). Next, \(\arctan\dfrac{1}{-\sqrt{3}}=-\,\dfrac{\pi}{6}\) which is in quadrant IV. However, \((-\sqrt{3},1)\) is quadrant II. So we add \(\pi\) and conclude: \[ \theta=\arctan\dfrac{1}{-\sqrt{3}}+\pi =-\,\dfrac{\pi}{6}+\pi=\dfrac{5\pi}{6} \] So a pair of polar coordinates is \(\left(2,\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\right)\).

For the point \(P\) with rectangular coordinates \((-\sqrt{3},1)\), find polar coordinates for \(P\) with a negative \(r\).

Add or subtract \(\pi\) from the angle and reverse the sign of the radius.

\(\left(-2,\dfrac{11\pi}{6}\right)\) or

\(\left(-2,-\,\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right)\)

Other answers are possible.

One pair of polar coordinates is \(\left(2,\dfrac{5\pi}{6}\right)\).

We add or subtract \(\pi\) from the angle and reverse the sign of the radius.

So the alternate coordinates are:

\[

\left(-2,\dfrac{11\pi}{6}\right)

\qquad \text{or} \qquad

\left(-2,-\,\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right)

\]

Now you can add any multiple of \(2\pi\) to the angle.

A point \(Q\) has polar coordinates \((-2,\dfrac{3\pi}{4})\). Obtain a pair of rectangular coordinates for \(Q\).

When converting from polar to rectangular coordinates, it does not matter if the radius is positive or negative. The formula will automatically put the point in the correct quadrant. We compute: \[ x=r\cos\theta =-2\cos\dfrac{3\pi}{4} =-2\left(-\,\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) =\sqrt{2} \] \[ y=r\sin\theta =-2\sin\dfrac{3\pi}{4} =-2\left(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) =-\sqrt{2} \] Therefore, the rectangular coordinates are \((x,y)=(\sqrt{2},-\sqrt{2})\). We notice this point is in the quadrant IV, which is correct.

Find the rectangular coordinates for the point \(R\) whose polar coordinates are \((6,-\,\dfrac{3\pi}{4})\).

\((-3\sqrt{2},-3\sqrt{2})\)

We compute: \[ x=r\cos\theta =6\cos\left(-\,\dfrac{3\pi}{4}\right) =6\left(-\,\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) =-3\sqrt{2} \] \[ y=r\sin\theta =6\sin\left(-\,\dfrac{3\pi}{4}\right) =6\left(-\,\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) =-3\sqrt{2} \] Therefore, the rectangular coordinates are \((x,y)=(-3\sqrt{2},-3\sqrt{2})\). We notice this point is in the quadrant III, which is correct.

Heading

Placeholder text: Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum Lorem ipsum